OPERATION COTTAGE AT 75, OR THE TIME THE CANUKS WERE REALLY WELCOME IN ALASKA

Operation Cottage at 75: The Time the Canucks Were Really Welcome in Alaska

Operation Cottage, a joint American-Canadian military action during World War II, marks its 75th anniversary, highlighting a unique moment of cooperation and camaraderie between the two nations. In August 1943, Allied forces launched this operation to recapture the Aleutian Island of Kiska from Japanese forces. The Canadians, known affectionately as “Canucks,” played a significant role alongside American troops in this endeavor. Despite the harsh Arctic conditions and challenging terrain, the operation showcased the strength and unity of the Allied forces.

The operation, although ultimately successful, is remembered for its unexpected twist. Upon landing, the Allied troops discovered that the Japanese had secretly evacuated the island weeks earlier, leaving behind only booby traps and abandoned equipment. Despite the lack of direct combat, the mission was fraught with danger, leading to numerous casualties from friendly fire and accidents. The operation underscored the complexities and unpredictabilities of wartime strategy and the harsh realities of warfare in such remote and unforgiving environments.

Today, Operation Cottage is celebrated not only as a strategic victory but also as a testament to the strong bond between the United States and Canada. This historical collaboration is commemorated through various events and exhibitions, serving as a reminder of the shared sacrifices and enduring friendship between the two nations. As we look back 75 years, the legacy of the Canucks’ bravery and the warm welcome they received in Alaska continues to inspire and honor their contribution to the Allied war effort.

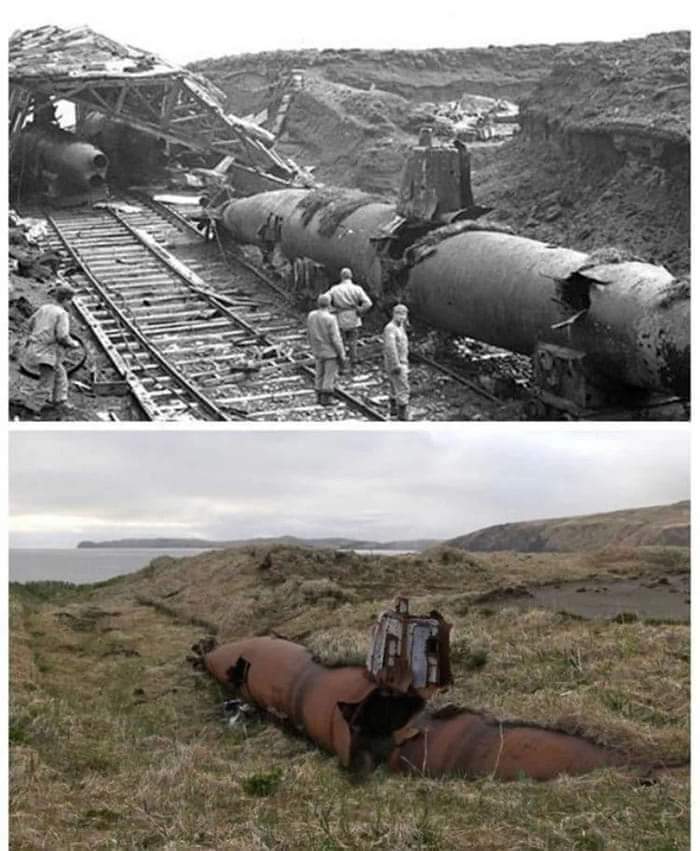

Inside view, looking seaward, of covered, Japanese submarine beaching railway, tracks leading to waterfront; a soldier passes large submarine handling cradles on left; warships are visible through opening.